Come winter and the attention of the entire country shifts to Delhi’s hazy skies. A kali-peeli taxi driver in Mumbai, last week asked, “Do you find it difficult to breathe in Delhi? We are lucky, we have sea. Sea absorbs everything”. And he added, “People in Mumbai use public transport even if they have cars; maybe that makes the difference”. Our response was as blurry as Delhi’s early mornings.

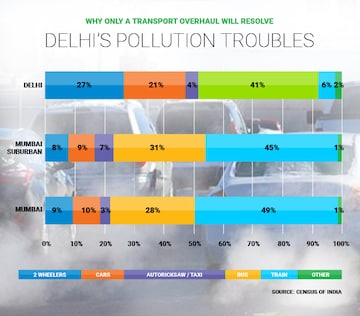

The reality is that Delhi surely has far more private vehicles (cars and two-wheelers), than Mumbai. As of now, both of these metropolises have more than 20 million residents; Greater Mumbai is predicted to have around 23 million residents by the end of 2018 and Delhi NCR a bit more than 20 million.

Delhi, however, has nearly four times the registered cars and two-wheelers i.e., about 420 registered cars and two-wheelers per 1,000 persons, compared to 110 in Mumbai. Nearly 75 percent employees in Mumbai travel to work by public transport compared to 45 percent in Delhi.

Mumbai may not be a benchmark for implementing best air quality practices, but its reliance on various modes of transport makes it a self-sufficient metropolis. The key perhaps lies in a public transport system that is accessible, affordable, and reliable—something that Mumbai can boast of but is in dire need of an upgrade.

Delhi has been making huge investments in building a robust metro rail system. However, despite the recent opening of a section on the Pink line that increased the network to 314 km, the metro system carries merely 5-6 percent of the total commuters in the national capital region. A city with 20 million residents cannot depend on a lop-sided investment in a metro rail system, but would need to divert its attention to the other critical section of city’s public transport system: buses.

Poor Public Transport System

The bus system in Delhi has failed to meet the growing demands of the city. The last thing that one would expect from one of the largest metropolises in the world is a declining city bus fleet. Delhi Transport Corporation’s (DTC) fleet declined to 4,352 buses in 2015-16 from 5,584 buses in 2011-12, as per official data. Fewer buses imply lower ridership; and not surprisingly the average daily ridership on DTC buses has taken a hit from 4.4 million to 3.5 million during this period.

While the addition of cluster buses has helped increase the number of buses on the roads, for a city that needs about 12,000-15,000 buses, these trends are worrisome, not just from the perspective of vehicular pollution, but also from the perspective of declining productivity and quality of life. Delhi needs to revamp its public transportation system if the government is serious about addressing vehicular emissions and congestion.

It is also the time that the city makes an aggressive transition to clean city buses to ensure that when 40-50 percent of the trips occur in the city, they have zero tailpipe emissions. It shouldn’t be difficult to initiate this transition. The city could immediately implement pilots of anywhere between 100-200 electric buses in the next 3-4 months followed by a full-scale deployment on the order of 5,000 electric buses in the next two years.

Will Transition To Electric Buses Help?

Delhi should aim for a complete transition to electric buses in the next three years. For a city that has gained the dubious distinction of the world’s pollution capital, such a bold step is not desirable, but essential.

Electric buses need not create an economic burden on the city. Expert analysis now shows that the total cost of ownership of electric buses is lower than combustion engine buses today, with costs predicted to fall further with the steep fall in costs of batteries.

While some studies have found that overall vehicular contributions of PM 2.5 are comparatively small, it is important to remember where the particulate matter is released. Vehicle tailpipe emissions are released at street level, just where pedestrians and citizens are most likely to absorb them, signalling disproportionate impact relative to other sources. It is also important to exercise control over sources of pollution that are within the city’s sphere of influence. While in many cases crop burning, dust and other sources of particulates lay outside the jurisdiction of the city, the portfolio of public transportation offerings lies squarely within the city administration’s domain.

Disincentivising the use of private, ageing, and polluting vehicles would be another bold step for Delhi. It is time that Delhi increases road tax on all new internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, be it cars, two-wheelers, auto rickshaws, taxis or commercial vehicles. Additionally, there is an urgent need to increase parking fees, as already proposed in addition to ensuring strict phasing out of and penalties on old and polluting vehicles.

More importantly, the city needs to use the revenue from disincentivising ICEs and parking to finance the clean bus system, non-motorised transport infrastructure and other initiatives such as public bicycle sharing that are critical for transitioning the mobility trajectory of the city. Delhi’s transportation system is at an inflection point, and longs for improvement in first and last mile connectivity, which should also be a focus for future mobility investments in the city.

Limiting Registration Of Private Vehicles

Lastly, the Delhi administration needs to show political will and stop shying away from taking the bold step of restricting registration of private vehicles, especially the second/third car and two-wheelers in a household. Of every 100 households in the city, nearly 30 own one or more cars, while 50 own one or more two-wheelers. The city has been registering 16,000-17,000 cars monthly, compared to 5,000-6,000 in Mumbai with a per capita income that is at par.

Global experience indicates that to control a growing population of private vehicles, cities have to resort to schemes like vehicle quota system that limit the number of vehicles being registered monthly/annually in the city.

Several cities in China have adopted such schemes. Beijing, for example, has been implementing a license plate lottery scheme since 2004. Over the years, the city hasn’t allowed more than 10,000 to 12,500 cars to be sold each month. In fact, this quota has been made more stringent over the years.

About 2.9 million applicants in Beijing were competing for 40,000 car licenses in 2018. The result is that despite a very similar population of 20 million people and per capita income levels nearly 3.5 times that of Delhi, Beijing has been able to restrict its car ownership to about 50 cars per 100 households compared to about 90 in Delhi.

Beijing and other Chinese cities have moved a step ahead. They have used this policy instrument to not only contain the growth of cars but also encourage adoption of clean cars. According to Bloomberg New Energy Finance, the six Chinese cities - Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, Tianjin, Hangzhou and Guangzhou - which implement vehicle quota schemes accounted for 40 percent of China’s electric car sales in 2017.

Delhi’s air cannot be cleaned through temporary measures. Delhi can learn from China’s progressive policy measures that not only decouple urban and vehicle growth but encourages adoption of cleaner vehicles.

The authors are principals at Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI) and co-lead RMI’s India practice. The views expressed are their own.

First Published: Jan 8, 2019 6:07 AM IST

Check out our in-depth Market Coverage, Business News & get real-time Stock Market Updates on CNBC-TV18. Also, Watch our channels CNBC-TV18, CNBC Awaaz and CNBC Bajar Live on-the-go!

Prajwal Revanna's father in custody for alleged kidnapping and sexual abuse

May 4, 2024 7:53 PM

Delhi, Indore, Surat and Banswara — why these are the most challenging domains for Congress internally

May 4, 2024 1:53 PM

Congress nominee from Puri Lok Sabha seat withdraws, citing no funds from party

May 4, 2024 12:00 PM

Lok Sabha Polls '24 | Rahul Gandhi in Rae Bareli, why not Amethi

May 4, 2024 9:43 AM