Last week’s monetary policy statement was noteworthy for what it did not contain. For the record though, it was the second straight policy where the MPC continued its ‘accommodative’ stance but without any rate cut. But there were two notable announcements outside the formal policy statement. First was the announcement of Long-Term Repo Operations (LTROs). Accordingly, banks will now have access to Rs 1 trillion of liquidity from the RBI at the policy rate (5.15 percent) for a period of up to three years. As a comparison, the current one-year CD rate (the rate at which banks borrow from each other) is 6.1 percent or almost 100 bps higher. The second was a push for banks to lend to certain sectors by giving sector-specific relaxations in CRR. Both these are on top of special OMOs (operation twist) from the RBI in December in which it bought long-dated bonds and sold short-term bonds. While the RBI has in the past pursued sector-specific interventions, the other two are new policies from the RBI and marks the central bank’s entry into the realm of ‘unconventional’ monetary policy.

Conventional monetary policy is all about the central bank setting a policy rate which sets the floor for the interest rate structure in the economy. All other interest rates get derived from it through the addition of various premia – term premia, risk premia, liquidity premia, etc. This is how the RBI has been generally conducting monetary policy until a couple of months back. The repo rate is the policy rate which is set by the RBI and the overnight inter-bank call money rate is the rate the apex bank targets to keep as close to the policy rate as possible. And the RBI has done this efficiently – the overnight inter-bank call money rate has generally very closely tracked the policy rate. So, the RBI has achieved the objective of monetary policy in conventional terms.

Many limitations

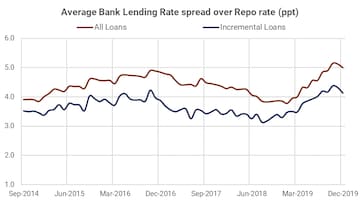

But there are limitations to this conventional monetary policy. The biggest one being that the RBI has no control over the various premia that get added onto to the policy rate. It can only influence them through either public statements or provision or restriction of liquidity. But its ability to influence these is limited. Thus, effective interest rates in the economy can diverge significantly, both directionally and in absolute terms, from the stance of the monetary policy. And this is exactly what has been happening in India for the last several months. The average lending rate charged by banks on fresh loans is currently 410 bps above the repo rate (as of December 2019) and the average lending rate on all outstanding loans is 500 bps above the repo rate. Both these spreads are about 60 bps above the median and are close to the highest they have been in the last 5 years, as shown in the chart below. This is the proverbial problem of inefficient (slow) monetary transmission in India.

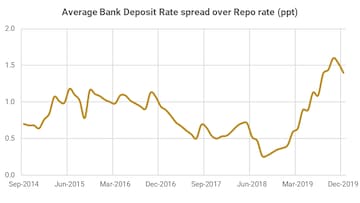

There are several reasons why this is happening, but one important reason is that even deposit rates have remained elevated relative to the policy rate. Current average deposit rate being paid by banks (on all outstanding deposits) is 140 bps above the policy rate, again close to the highest in the last 5 years. Over the past 5 years, the median spread has been around 80 bps, so the current spread is around 60 bps higher than the average. So effectively, relative to the policy rate, both lending and deposit rates are much higher than they have been in the last few years.

So, the unconventional monetary policy that we are seeing from the RBI is an attempt to correct this anomaly. There is very little the RBI can do about risk premia lenders are charging. But the RBI can influence the term-premia and liquidity-premia. The ‘operation twist’ launched in December and the long-term repo auctions announced last week are steps to reduce the term-premia and liquidity-premia in the market.

A logical question to ask is why has the RBI taken this route of unconventional monetary policy? Could it not just lower the policy rate further and even if the spreads remain unchanged, the effective lending rate in the economy would have come down. Why is the RBI treading down this unconventional path? A couple of factors explain this decision. First and probably the most important being that the problem of slow monetary transmission in an easing cycle. This is real but also an old problem. The RBI has through successive measures tried to improve transmission. These include moving away from Prime Lending Rate to a Base Rate and then from the Base Rate to the MCLR. More recently the RBI has mandated linking of lending rate to an external benchmark. But the process of transmission remains slow. Given how weak the economy is, the RBI wants the monetary transmission to happen faster. The unconventional policy, apart from a tangible intervention in the market, also sends out a message to market participants that the RBI will do ‘whatever it takes' to ensure interest rates in the economy are lower. This is an important messaging to all market participants. Secondly, the RBI probably thinks cutting the policy rate when inflation is running above 7 percent is unwise from a messaging perspective.

A lot of people have compared the RBI’s announcement of LTROs with the ECB’s LTROs just after the global financial crisis. While there are similarities, both the Eurozone economy and the Indian economy are very weak currently, there is a major difference and that is inflation. The ECB did not have to worry about inflation when it announced its LTROs. Indeed, at points of time post the GFC, the Eurozone economy was at risk of deflation. In contrast, the last print for inflation in India was 7 percent, well above the upper threshold set for the RBI. And as per RBI's forecast inflation is likely to remain above 5 percent, higher than the 4 percent target, over the next few months. Infusing large doses of easy money when inflation is running well above target is a risky move.

Aggressive liquidity infusion

The other issue with this aggressive liquidity infusion is that if the economy is facing structural headwinds, there is little that the monetary policy can achieve, on its own. Japan and the Eurozone are good examples of growth remaining weak despite zero or negative interest rates. Easy or even ultra-easy monetary policy is not a substitute for structural reforms from the government. Easy monetary policy is akin to a steroid: It can give short-term impetus, but the economy will soon get used to it (and thus will be required in larger dose next time around) in the absence of structural reforms. Monetary policy on its own cannot solve our structural bottlenecks.

There is also another fundamental issue with the path the RBI has taken. And it is that the monetary policy now bypasses the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) since liquidity decisions are in the domain of the RBI and not the MPC. The reason for setting up the MPC was to have more people delve on the appropriate monetary policy than just a single person (the RBI governor). Now with this focus on liquidity rather than policy rate, monetary policy has moved back into the sole domain of the RBI and by implication the RBI governor. While theoretical, the MPC can vote down the RBI governor in interest rate decision but the RBI governor using liquidity tools to frustrate the MPC's rate decision. It is well worth considering if liquidity operations should also move on to the domain of the MPC.

To sum up, the RBI has embarked on a bold new path. That it is trying to accelerate the pace of monetary transmission is positive. Going by the average of last 5 years, there are about 50-100 bps of compression that lending and deposit rates can see to be consistent with the current level and stance of monetary policy in a conventional sense. But the new path is not without risks given the less than benign inflation backdrop. And given the long-term nature of the liquidity infusion siphoning this liquidity off, should inflation trajectory surprise on the upside, will be a challenge and could cause dislocations in the market.

Ashutosh Datar is the Founder of IndiaDataHub.com, an online platform that brings together all the public data (economic, social, financial) concerning India in a user-friendly analytical app. Before founding IndiaDataHub, he was with IIFL Institutional Equities for over a decade as their Strategist and Economist. Read his columns here.

First Published: Feb 12, 2020 6:00 AM IST

Check out our in-depth Market Coverage, Business News & get real-time Stock Market Updates on CNBC-TV18. Also, Watch our channels CNBC-TV18, CNBC Awaaz and CNBC Bajar Live on-the-go!

Supreme Court says it may consider interim bail for Arvind Kejriwal due to ongoing Lok Sabha polls

May 3, 2024 4:57 PM

10% discount on fare on Mumbai Metro lines 2 and 7A on May 20

May 3, 2024 2:40 PM