The idea that art is open to interpretation, invoking different meanings and appreciation in ways that the creator had not intended is well established. By definition what constitutes art is in itself subjective. One increasingly shared perception, however, uniting a significant part of the art eco-system is its utility as an effective and discreet wealth management tool. As many countries tighten tax legislation, introduce capital controls and enforce regulation in respect to cross-border transactions, an ever-growing number of High Net Worth’s (HNW) are seeking to shield their liquid assets from authorities. One response has been to financially manoeuvre into solid, capital-appreciating assets. So how has this been enabled within a 100 percent legal framework and is it more of a case of life imitating art that’s driving its economy?

Freeports

Freeports are located in tax-free zones separate of any jurisdiction. They are used to store high-end art outside the scope of any regulator and are often described as the physical equivalent of a Swiss bank account. Freeports form an integral component of the art investing trade, enabling a network of high value, discreet, tax-exempt transactions. Despite some of the most significant warehouse sites situated in Geneva, Shanghai, Singapore and Delaware—they are considered offshore and not of residence to the country. This allows legitimate investors to avoid any wealth or inheritance taxes in their home countries but can nonetheless benefit from financial engineering infrastructure. This includes using art as collateral to buy other assets, or even more complex investment structures such as hedges, the buying and selling of risk, and reinsurance. Freeports constitute a multi-billion-dollar, multi-asset liquidity pool and provide the rails for the trade.

Buying low and donating high, the tax credit system

Unlike most other asset classes, the intrinsic value of art is highly subjective thus producing a pricing mechanism prone to idiosyncrasies. For instance, it's technically possible to inflate the price of an artwork, legitimately or otherwise, through an orchestrated auction among a team of bidders. This, in turn, is likely to raise the price of all art produced by that artist. Such practices have reportedly been employed to exploit the tax credit system which allows for the value of art donated to museums to be offset against the tax payable by an individual or company.

Theoretically, the system plays out by an HNW individual or a company first purchasing a large collection of art from an undiscovered artist at a relatively low price. It would then solicit a reputable art dealer to promote the new artist via exhibitions, campaigns and press features. Once the artist develops more notoriety, their work is placed at auction and bought at a far higher price by an inflated bid. As a result, the entire collection, on paper at least, is significantly more valuable and legitimised by historic sales figures. In reality, the new price of the collection could be a tough sell to other collectors but can nonetheless be donated to a museum for a higher charitable donation than originally bought at, and in the process lower the overall tax liability.

Emerging markets and a new class of buyers

Contemporary art is now the most dynamic and profitable segment of the entire art market. In 2000 the sector accounted for $92 million of auction turnover and 3 percent of the overall global art market. The Art Basel-UBS report now estimates this at $2 billion and 15 percent of the market, overtaking both the Old Master and 19th century.

An illustration of this growth can be seen when considering the works of Jean-Michel Basquiat. In 1998, he created the first contemporary artwork to fetch over $1 million, and in 2017 he again produced the most expensive contemporary piece ever sold. Between the two dates, Basquiat’s auction record rose from $1.7 million to over $110 million, multiplication by 65 in 20 years.

“Untitled” by the late graffiti artist-turned-expressionist painter Jean-Michel Basquiat sold for $110.5m at a New York auction. It places the Brooklyn-born Basquiat, who died in 1988 of a heroin overdose aged 27, as one of the most coveted artists in the segment alongside Francis Bacon, Pablo Picasso, and Andy Warhol

“Untitled” by the late graffiti artist-turned-expressionist painter Jean-Michel Basquiat sold for $110.5m at a New York auction. It places the Brooklyn-born Basquiat, who died in 1988 of a heroin overdose aged 27, as one of the most coveted artists in the segment alongside Francis Bacon, Pablo Picasso, and Andy WarholOther notable references include Andy Warhol’s 1963 screen print Liz, which could sell for $2 million in 1999 yet by 2007, pieces from the same series were selling for $24 million. From 2000–2019, the average price of a contemporary artwork had approximately tripled (going from $7,400 to $25,000). The segment is now the primary growth engine of the global art market.

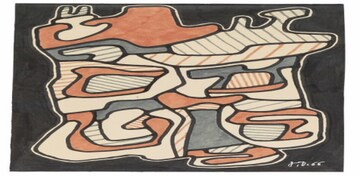

Jean Dubuffet, La Villa III sold for $25,000 in 2014. In 2020 it was again sold for $59,651. Total growth of 139%, 0r 17.1% annually.

Jean Dubuffet, La Villa III sold for $25,000 in 2014. In 2020 it was again sold for $59,651. Total growth of 139%, 0r 17.1% annually.In the book Big Bucks: The Explosion of the Art Market in the Twenty-First Century, art market reporter Georgina Adam explored the forces that propelled this stratospheric rise. In it, she cites two key factors. The first was the expansion of the base of potential buyers: The fall of communism in Eastern Europe and economic liberalisation in countries like China and India created a new wave of billionaires eager to spend. In China, demand has also been boosted by a government-sponsored museum building boom as well as the general development of an art business culture that includes the growth of specialised investment funds.

The second major change was a shift in the core of the auction house business, away from Old Masters and Impressionists. Historically, selling contemporary art had been the province of galleries and private dealers. But major auction houses such as Sotheby’s and Christie’s recognised that promoting the contemporary market could open up vast new revenue streams.

In Art Economics, Dr Clare McAndrew also notes an interesting facet in the composition of Asian buyers, which could also correlate to the specifically strong demand for contemporary art in the region, and art as an asset class more generally. Her studies found that Millennial collectors made up just under half (45 percent) of the high-end spenders or $1 million-plus items, demonstrating a notable contrast to the age of the average western buyer of a similar value.

Auction houses

The evolvement of auction houses to new buyer markets and their part in the growth of the art economy cannot be underestimated. The sector is dominated by Christie's and Sotheby’s followed by China Guardian, Poly Group, Bonhams, and Phillips. HNW clients are now offered a range of globally accessible financial services including collector lines of credit and selling works with third-party guarantees, thus further enabling demand and fuelling prices. Moreover, art reporter Georgina Adam recalls a distinct shift in the operations and culture of auction houses when Christie’s was purchased by Kering in 1998, the owner of the European retail conglomerate whose brands include Gucci, Saint Laurent, and Balenciaga. She describes how they began to function more like luxury brands from that point, aggressively promoting a never-ending flow of new inventory, and with it, a jet-set lifestyle of multi-million-dollar auctions, exclusive gallery dinners, and VIP art fair vernissages.

The increasing prominence of art as an asset class will no doubt add to its commodification. Many enterprises like Maecenas now pool investor resources to buy and sell options for fractional ownership in artworks, such as shares on a stock exchange. As the accumulation of total global wealth continues to grow, so does the machinery of the art economy with key actors within it, from freeports to auction houses motivated to put ever more capital to work.

—Shiv Morjaria is a derivatives lawyer for an investment bank and tech entrepreneur. The views expressed are personal and do not constitute advice

(Edited by : Ajay Vaishnav)

First Published: Jan 18, 2021 6:10 PM IST

Check out our in-depth Market Coverage, Business News & get real-time Stock Market Updates on CNBC-TV18. Also, Watch our channels CNBC-TV18, CNBC Awaaz and CNBC Bajar Live on-the-go!

Telangana CM violated poll code, defer Rythu Bharosa payment, says Election Commission

May 7, 2024 9:01 PM

Lok Sabha Election 2024: How Indian political parties are leveraging AI

May 7, 2024 6:59 PM