Here are some basic questions that take us deep into the fascinating world of banking and money.

Why don’t banks lend out the current ‘banking liquidity surpluses’ to clients, rather than dumping them with the RBI? Before June 2019, banks were running “liquidity deficits”. Why didn’t banks then raise client deposits to fund the deficits, rather than constantly borrowing from the RBI?

Are our banks lazy, preferring to deal with the RBI rather than do business with their clients?

Let’s try and address these and other related questions in this explainer.

Balance sheet of Indian banking system

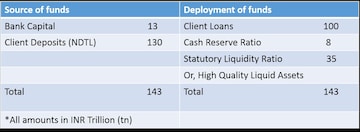

To start with, consider Table 1, an admittedly simplistic snapshot of the balance sheet of the total Indian banking system, at the start of a typical day in today’s context.

Banks hold Rs 130 trillion of liabilities (client demand and time deposits) and Rs 13 trillion of capital, which fund Rs 100 trillion of client loans and Rs 43 trillion of reserve assets.

The reserve assets are in two forms. The first is Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR) balances with the RBI. As the banker to banks, RBI mandates that banks must maintain a minimum CRR of 4 percent of Net Demand and Time Liabilities (NDTL). In table 1, therefore, against Rs 130 trillion of deposits, banks must maintain at least Rs 5.2 trillion of CRR.

The second reserve is government securities held to meet Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR) and High Quality Liquid Assets (HQLA) requirements. The RBI mandates a minimum SLR of 18.25 percent of NDTL, and sufficient HQLA to cover 30 days of expected outflows. Banking outflows, and hence HQLA, is not a static percentage of NDTL – it depends on the type and tenor of banking deposits and loans. For now, let’s assume that the minimum combined SLR and HQLA requirement is 23 percent of NDTL, or in Table 1, Rs 29.9 trillion.

We will refer to Table 1 in all the illustrations that follow below.

What are banking liquidity surpluses?

At the start of day, the banking system has surplus CRR balance of Rs 2.8 trillion over the statutory requirement of Rs 5.2 trillion. This is the ‘banking liquidity surplus’.

Instead, if banks expected to end with CRR balances less than the statutory requirement, that would constitute a ‘banking liquidity deficit’.

In addition, banks have surplus SLR/ HQLA of Rs 5.1 trillion over the requirement of Rs 29.9 trillion. Between CRR and SLR/ HQLA, therefore, the system has total excess statutory reserves of Rs 7.9 trillion.

Do banks – lazily or otherwise - lend to or borrow from the RBI each day?

Not really.

The RBI’s daily Liquidity Adjustment Facility (LAF) window merely allows banks to convert one form of statutory reserve to another.

In case of a CRR shortfall, banks can convert excess SLR/ HQLA into CRR at the RBI’s LAF repo window. They effectively pay the LAF policy repo rate for this transformation, currently set at 5.15 percent.

Likewise, banks can convert surplus CRR balances into SLR/ HQLA at the RBI’s LAF reverse repo window, earning them the LAF policy reverse repo rate of 4.90 percent, against the 0 percent otherwise payable on CRR balances.

Banks thus need only to worry about maintaining overall reserves - or 27 percent of NDTL. The breakup between 23 percent SLR/ HQLA and 4 percent CRR can be adjusted by accessing the RBI LAF windows.

How does the banking system fund fresh loans?

Suppose an eligible borrower seeks a fresh loan of Rs 10 trillion, much higher than the Rs 7.9 trillion of excess statutory reserves with banks. Can the banking system provide this loan?

The first thought may well be that to disburse the loan, the system must create space - maybe by selling some government securities and/ or by raising fresh deposits.

Here is where the beauty of banking and money creation comes in. Every loan given out by the banking system funds itself, by creating its own deposit.

After all, when a bank gives out a loan, it credits the account of borrower and creates a fresh bank liability. When the borrower then deploys the funds, the funds merely flow into other beneficiary banking accounts and stay in the banking system as client deposits.

With every loan given out, the banking system thus creates new money that can chase goods and services.

Are there funding constraints to lending at all?

There are indirect constraints to lending, through statutory reserve and capital requirements.

Because lending creates deposits, with every loan disbursed, the need for statutory reserves goes up. On the additional Rs 10 trillion of deposits created above, Rs 2.7 trillion of additional reserves would be needed. This would not be a problem for now, since this is well within the Rs 7.9 trillion of surplus reserves available. In fact, banks can disburse fresh loans of up to Rs 29.3 trillion today - a whopping 29.3 percent of outstanding loans - and still hold enough statutory assets.

Even if there were no additional reserves available to start with, all that banks would need to do to disburse the Rs 10 trillion would be to buy an additional Rs 3.7 trillion of government bonds (SLR/ HQLA), which in turn would increase deposits by a like amount. A total of Rs 13.7 trillion of deposits would then be created, and the Rs 3.7 trillion of additional SLR/ HQLA purchased would cover the additional statutory reserves required against this.

In summary, maintenance of statutory reserves is not a constraint, if the issuers of SLR/ HQLA - the government in our case - is borrowing in ample measure.

The other constraint is bank capital. As the size of the loan book increases, the capital needed by banks would increase.

Of course, there are other non-funding constraints to loan growth that centre around trust, incentives, and demand for credit. But such constraints cannot be primarily addressed by balance sheet measures.

Can banks alter banking liquidity?

Aside from the daily LAF adjustment across SLR/ HQLA and CRR, there are five routes through which the CRR balances of the banking system are more durably altered.

The government maintains its accounts with the RBI, outside of the banking system. Payment of taxes, therefore, reduces bank deposits and CRR balances, while increasing government balances with the RBI. Conversely, government spending reduces government balances with the RBI, and increases bank deposits and CRR balances.

Withdrawal of currency notes by banking clients reduces banking deposits, reduces CRR balances, and increases currency in circulation. Conversely, deposit of currency notes by customers increases banking deposits, increases banking CRR, and reduces currency in circulation. As an aside, currency notes are effectively our zero-interest demand deposits placed with the RBI.

Foreign currency inflows create banking deposits and banking foreign currency assets. If the RBI purchases foreign currency, these banking foreign currency assets are then converted into CRR balances. Conversely, foreign currency outflows that are funded out of RBI foreign exchange reserves reduce banking deposits and CRR balances.

Open Market Operation (OMO) bond purchases by the RBI from banks reduce banking SLR/ HQLA and increases CRR balances. Conversely, OMO bond sales by the RBI to banks increase banking SLR/ HQLA and reduce CRR balances.

Finally, the RBI can impact all banking statutory surpluses by altering the minimum level of SLR, HQLA and CRR that banks need to maintain.

None of these routes are really controllable by banks. In other words, banks cannot really alter systemic banking liquidity.

The only entity that can and does consciously modulate the level of banking liquidity is the RBI, through bond OMO, foreign exchange intervention, and setting the level of statutory reserves that banks must maintain.

But can’t individual banks adjust their liquidity situation?

They can. But overall systemic liquidity cannot be altered by banks, even as banks pass the liquidity parcel amongst themselves.

The system cannot “lend away” liquidity surpluses – as described earlier, every loan creates its own deposit, and does not directly reduce banking liquidity. At best, because every fresh loan creates a deposit, the CRR requirement increases. But to reduce the current liquidity surplus of Rs 2.8 trillion to zero through this route, banks must lend a whopping Rs 70 trillion, or 70 percent of the current loan book.

Likewise, selling government bonds to entities such as insurance companies or mutual funds only reduces banking deposits and bank SLR/ HQLA levels – it does not change banking CRR balances.

In summary, the banking system must live with the liquidity hand that they are dealt by the RBI. It cannot be blamed for not altering the liquidity context.

If banks don’t need banking liquidity to make loans, what is the use of maintaining systemic surplus or deficit liquidity?

Liquidity surpluses or deficits impact money market and risk-free interest rates and can encourage - or discourage - client lending.

With a consistent systemic liquidity surplus, individual banks would try and pass the liquidity surplus amongst themselves, buying risk-free assets or giving out fresh loans to earn better return than the low RBI LAF reverse repo rate. While this would do nothing to alter overall system liquidity, it would drive down short-term interest rates towards the overnight rate and encourage fresh lending.

Conversely, when the system has a consistent liquidity deficit, individual banks would chase deposits and sell short-term assets to try and pass on the deficit to someone else. While again this would do nothing to alter system liquidity deficit, it would drive up short-term rates and discourage fresh client lending.

In short, a consistent liquidity surplus (deficit) ensures that the system chases their own tail in a futile manner to stay neutral on liquidity. This ends up driving short-term rates down (up), while encouraging (discouraging) fresh loans.

Summary

The banking system does not borrow clean funds from (or lend clean funds to) the RBI. The daily LAF repo and reverse repo windows only allows the system to transform excess SLR/ HQLA into CRR and vice versa.

The banking system does not need liquidity surpluses to disburse fresh loans, because fresh loans create their own fresh deposits. Bank lending creates fresh money to chase goods and services.

The balance sheet constraints to bank lending centre around statutory reserves and capital. The need for statutory reserves is easily managed as long the government is borrowing in adequate quantities.

Banks cannot really alter the system liquidity status. The routes for increase or reduction in banking liquidity – government spending, the demand for currency, RBI foreign exchange intervention, bond open market operations, and statutory reserve limits set by the RBI – are largely outside of bank control. The RBI can and does consciously set the liquidity context by use of the routes under its control.

The banking system cannot really “lend away” liquidity surpluses, nor can it actively source deposits that reduce any liquidity deficits.

The banking system chases its own tail, trying to remove large liquidity surpluses or deficits. Liquidity surpluses (deficits) reduce (increase) short term rates and encourage (discourage) fresh client lending.

Ananth Narayan is Associate Professor-Finance at SPJIMR.

Our thanks to Prof Anant Narayan who has explained the concept in great detail in this article.

First Published: Jan 28, 2020 12:49 PM IST