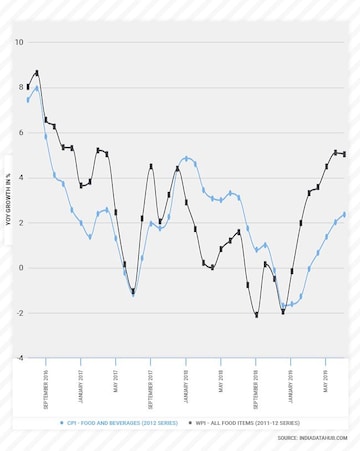

Food inflation has been remarkably subdued for the past few years. In the last three years, food inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for food and beverages has averaged just 2 percent, well below the average since 2012 of 6 percent. For the economy, sustained low food inflation is a mixed blessing. On one hand, it allows overall inflation to remain low enabling monetary policy to be accommodative. But on the other hand, by depressing rural incomes, it impacts rural consumption. That said, food inflation has been on an upswing in the last few months. This is most visible in the Wholesale Price Index (WPI) rather than the CPI. While the CPI for food and beverages has increased from a low of -1.7 percent in November to 2.4 percent in June, the WPI for primary foods has increased from a low of -1.7 percent to 5 percent during the same period and is the highest in more than two years. The divergence between CPI and WPI partly reflects the divergent weights in the two series, but also the lag in transmission of higher wholesale prices to retail prices.

Food inflation is on the rise

Monsoon rainfall YTD (July 27) is 14 percent below the long-term average. The distribution of rainfall too has been less than optimum. Reflecting this, the acreage under the Kharif crop is 8 percent below normal as of late July with almost half the sowing season having passed. In categories like pulses and coarse cereals, the acreage till date is more than 10 percent below normal. While actual acreage at the end of the season will not be this low, even a 2-3 percent lower acreage will, coupled with lower yields due to the subpar distribution of rainfall, mean a material fall in output. And this will only add to the food inflation which is already increasing.

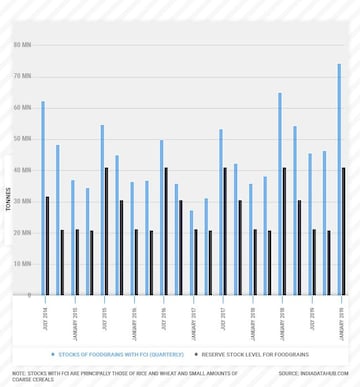

Food grain stocks with FCI are the highest in the last few years

The point is that food inflation after remaining low for several years is on an upswing. Now the government can take steps to control food inflation. On one hand, the government can proactively use food grains stocks to control domestic prices. In rice and wheat, the current stocks with the Food Corporation of India are more than 100 percent and 60 percent above the buffer stock norms. Foodgrain stocks with FCI as of July 1 this year is the highest in the past several years. In pulses, media reports suggest that stocks with Nafed are at record highs. In the case of Arhar (Tur), the principal Kharif pulses crop, the stocks are at almost 20 percent of production. The government can also use imports to augment domestic supply. In categories like pulses or oilseeds, India is already a large importer (relative to domestic production). The government has in the past encouraged imports to cool down domestic prices.

The point is that food inflation after remaining low for several years is on an upswing. Now the government can take steps to control food inflation. On one hand, the government can proactively use food grains stocks to control domestic prices. In rice and wheat, the current stocks with the Food Corporation of India are more than 100 percent and 60 percent above the buffer stock norms. Foodgrain stocks with FCI as of July 1 this year is the highest in the past several years. In pulses, media reports suggest that stocks with Nafed are at record highs. In the case of Arhar (Tur), the principal Kharif pulses crop, the stocks are at almost 20 percent of production. The government can also use imports to augment domestic supply. In categories like pulses or oilseeds, India is already a large importer (relative to domestic production). The government has in the past encouraged imports to cool down domestic prices.The government has tools at its disposal to try and contain food inflation. The important questions from a policy perspective are not whether the government has tools or what tools it will use to contain food inflation but how effective the measures will be and more importantly, whether the government should try and contain food inflation in the first place.

The answer to the first question of whether the government will succeed in containing food inflation depends to a large extent on the extent of rainfall deficit, the extent of lower production and the final cropping pattern. A modestly lower production can, of course, be handled through imports and stocks but a large drop in production cannot. Similarly, if production decline were to manifest in categories like coarse cereals or fruits and vegetables where there is little or no stocks with government agencies and limited scope for imports to augment domestic production, then there is precious little the government can do. But a key factor at play is the state of the agriculture cycle. In 2014 and 2015 when we had back to back droughts and food inflation remained under control, the agriculture cycle had tailwinds. Years of sustained double-digit food inflation had made agriculture profitable and thus farmers had incentives to invest in the crop even in a drought year to try to offset the impact of adverse weather. Production growth was also strong going into drought years. Foodgrains output had grown over 3 percent in 2013-14 the year before drought whereas last year (2018-19) foodgrain output declined modestly. In pulses, production fell 10 percent last year. In fruits and vegetables, the production is estimated to have been flat last year. So, the government efforts to contain food inflation this year will run into headwinds of the underlying agriculture cycle as against tailwinds in the case of the preceding drought year. This by itself will reduce the odds of government policy succeeding in containing food inflation. It is also worth remembering the experience of the last inflationary cycle when food inflation averaged over 10 percent for several years. The experience of that cycle shows that the ability of the government to materially influence a cycle is limited.

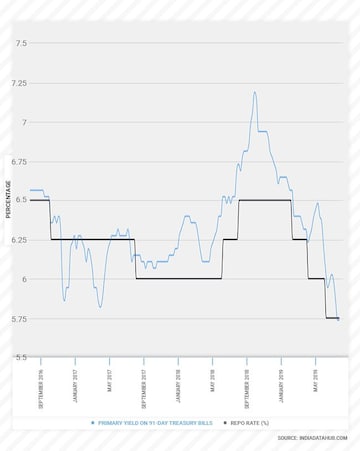

The more interesting question though is whether the government should try and contain food inflation. This is not a question about economic philosophy of whether the government should intervene in markets but rather a political question. Sustained low food inflation has created stress in rural areas and a below-normal monsoon will only aggravate it. Higher crop prices offset this stress partially. Not to all the farmers of course, but at least to some. But if the government were to clamp down on food inflation, this will only aggravate the rural stress. This is also bad for the overall economy since at the margin this also means that the hit to rural incomes will be larger than what it otherwise would be in the ‘natural course of events.’ But there is a flip side as well. The non-agriculture economy is slowing down and interest rate sensitive sectors such as real estate and automobiles are struggling. In this scenario, food inflation remaining low will, ceteris paribus, allow the RBI to cut interest rates. A 100bps fall in interest rates will, for example, be a material stimulus to the non-agriculture part of the economy. But this can only happen if food inflation remains low. If food inflation inches up, the RBI may very well have to reverse course and tighten monetary policy, increasing the headwinds for the non-agriculture economy. Thus, the decision of whether to try and aggressively contain food inflation comes down to which part of the economy (agriculture vs non-agriculture) the government wants to support at this point of time. And that is largely a political decision – a political choice driven by political objectives. It will be interesting to see what choices the government makes in the coming few weeks. As I have written before, the nature of the mandate for the government means that it can afford, from a political perspective, to ignore short-term considerations and focus on the structural issues facing the economy. The worst is to try and support both – contain food inflation, on one hand, to support the non-agriculture economy through monetary policy and support the agriculture economy through fiscal policy (loan waivers, higher cash transfers etc). Recent news from Karnataka suggests that this option is very much a possibility.

Short-term interest rates are below the policy rate

The last few years of low food inflation have lulled policy makers into believing that food inflation has structurally come down. Financial markets are starting to price in multiple rate cuts from the RBI with short-term interest rates falling below the policy rate. But as I wrote in this piece, there is nothing out of ordinary about the current phase of low food inflation. It is part of normal agricultural cycle. And it is only a matter of time before the cycle changes gears. And if the drought like conditions this year accelerate this process, the consequences of food inflation rising in an environment when rest of the economy is slowing will be significant. If food inflation were to rise from the current 1-2 percent level to 4-5 percent level in the next few months, CPI inflation will rise from current 3 percent level to 5 percent and the markets will then have to shift from thinking about the number of rate cuts the RBI will do to whether the RBI will increase interest rates. And given the state of the fisc (true fiscal deficit for the central government is estimated by the CAG to be at least 200bps higher than the reported number), there are no levers on the fiscal side to pull the economy out.

The last few years of low food inflation have lulled policy makers into believing that food inflation has structurally come down. Financial markets are starting to price in multiple rate cuts from the RBI with short-term interest rates falling below the policy rate. But as I wrote in this piece, there is nothing out of ordinary about the current phase of low food inflation. It is part of normal agricultural cycle. And it is only a matter of time before the cycle changes gears. And if the drought like conditions this year accelerate this process, the consequences of food inflation rising in an environment when rest of the economy is slowing will be significant. If food inflation were to rise from the current 1-2 percent level to 4-5 percent level in the next few months, CPI inflation will rise from current 3 percent level to 5 percent and the markets will then have to shift from thinking about the number of rate cuts the RBI will do to whether the RBI will increase interest rates. And given the state of the fisc (true fiscal deficit for the central government is estimated by the CAG to be at least 200bps higher than the reported number), there are no levers on the fiscal side to pull the economy out.Ashutosh Datar is the Founder of IndiaDataHub.com, an online platform that brings together all the public data (economic, social, financial) concerning India in an user-friendly analytical app. Before founding IndiaDataHub, he was with IIFL Institutional Equities for over a decade as their Strategist and Economist.

Read Ashutosh Datar's columns here.

First Published: Jul 31, 2019 6:00 AM IST

Check out our in-depth Market Coverage, Business News & get real-time Stock Market Updates on CNBC-TV18. Also, Watch our channels CNBC-TV18, CNBC Awaaz and CNBC Bajar Live on-the-go!

Supreme Court says it may consider interim bail for Arvind Kejriwal due to ongoing Lok Sabha polls

May 3, 2024 4:57 PM

10% discount on fare on Mumbai Metro lines 2 and 7A on May 20

May 3, 2024 2:40 PM