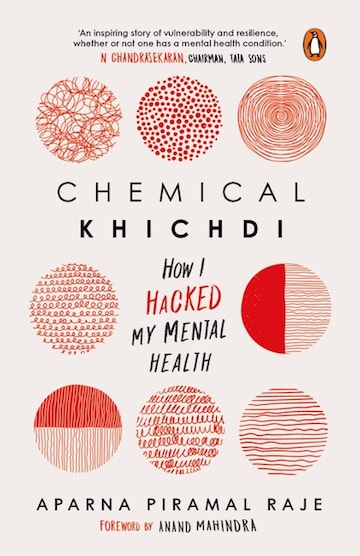

Aparna Piramal Raje’s new book Chemical Khichdi has a lot to offer. However, all of it boils down to one simple but important message: you can be bipolar and still be happy, successful, and go after your dreams, whatever they might be.

Raje hails from an illustrious business family and has led a life that looks ideal on the surface. But delve a little deeper and you’ll find out how her struggle with bipolar disorder threw her and everyone else around her into uncharted waters and how, despite living with it for over two decades now, she has, with remarkable resilience and grit, carved out a meaningful life for herself.

Chemical Khichdi is her second book. Divided into three parts, it throws light on the condition (definitions, identifications, triggers, factors), how to address it holistically, and how to see mental health and well-being as one. Armed with statistics, toolkits, helplines, personal journal entries, poetry, testimonials from family, friends, doctors, and colleagues, and other valuable resources, Chemical Khichdi dispenses essential dos and don’ts on how to be, with oneself and others, who may or may not be struggling with their mental health. Part memoir, part self-help guide, it uses the lens of bipolar disorder to show how to live.

In this exclusive interview, Raje discusses her love for writing, the seven therapies that Chemical Khichdi delves into in great detail, the books that have left an indelible impact on her, her thoughts on empathy and being non-judgmental, and how difficult it was for her to write a book with such searing transparency and radical honesty.

Q. You say that writing has always been your primary form of expression. When and how did you take to it? When did you realise that you could translate it into a career?

A. I enjoyed writing even in school and I pursued media internships while at college. My mother, Gita Piramal, is a bestselling author so I was lucky to learn from her. But given the family business (VIP luggage), I always thought of that as my natural career option, not writing. It was when I worked with my family’s office furniture business, about 20 years ago, that I started writing on design and business, on evenings and weekends, and that writing eventually turned into a column for the Mint. When I was on maternity leave with my older son, I realised I enjoyed managing ideas more than managing people and decided to translate writing into a full-time profession.

Q. In the book, you throw light on how working on a range of life arenas can help address the problem better. How much weight do you give to medical therapy and to these other therapies as an effective way to treat a mental health condition?

A. I give a lot to weight to these seven therapies as they constitute my path to healing and recovery. My conversations with medical experts, patients, and caregivers suggest that they have found these therapies useful for a range of mental health conditions, as they are drawn from everyday life and have universal application to anyone wanting to improve their mental health and wellness.

Medical therapies, such as drug therapy and talk therapy, are the starting point for treatment and recovery. Love therapy, which is the role of caregivers, underlines why mental health is a team sport. Allies, such as friends and other community members, offer the therapy of empathy. Work therapy outlines how to find a balance between work that is stressful and work that is therapeutic. Self-therapy talks about the need to have conversations with oneself, especially on the subjects of purpose, meaning, and dharma. Spiritual therapy has given me the tools to address the triggers that cause mood swings. Lifestyle therapy looks at the role of sleep, exercise, nutrition, and play, and why mental health is like a garden that one needs to attend to every day. Together, they represent a holistic approach to recovery – that has been my lived experience. Each individual should find the best combination for themselves, that is my hope from the book.

Q. For a subject as complex as mental health, you’ve written the book very simply. It’s easy to understand, enough to be read by both adults and children. What audience did you have in mind while writing? Were you also aiming at children? What kind of effort did you have to put in to make the writing as accessible as it is?

A. I’m so glad you found it accessible. As I’m not a trained mental health professional, I drew on my lived experience and tried my best to take the reader into my mind. I think writing for a newspaper for over a decade has also helped me to make my writing as simple and accessible as possible. I also read quite a few mental health memoirs before writing Chemical Khichdi, to understand the genre, the ground already covered, and the opportunities.

I was looking at anyone living with a mental health condition, and their caregivers, allies, mental health professionals, and colleagues — which is a lot of us. These challenges often begin in adolescence or with young adults. I’m not sure some themes in the book are appropriate for children, although there is some poetry specifically for them in the book.

Q. Which three books have left a deep impact on you? Which genre do you like to read the most?

A. I love to read fiction the most, but the three books that have left the deepest impact on me are all non-fiction, and kind of self-help. The first is How Will You Measure Your Life? by Clayton Christensen, which provides a helpful, insightful, and practical approach to answering a most philosophical question.

The second is Untamed by Glennon Doyle, which is an incredibly motivating and easy-to-read book, especially for women. It taps into universal truths holding women back from growing personally and professionally, with powerful metaphors and ideas.

The third is actually two books. The Holocaust of Attachment by Swami Parthasarathy, which I studied for a year in weekly classes. And also the Bhagavad Gita which I cannot claim to have read in its entirety, but whose single verses have changed my life. All of these have been a source of tremendous illumination and self-examination.

Q. In the book, you mention how there would be talks in the family about your bleak chances of getting married and becoming a mother. What were your thoughts then? What were your thoughts when you got married and had children? What are your thoughts now?

A. While these bleak prophecies were being discussed by others, I wasn’t aware of them at the time (in my 20s), so I just carried on with my life. I knew I had mood swings, but they were thought to be linked to personality and life circumstances then, not to a medical condition. When I started dating Amit (now my husband), I did tell him about them, but neither of us understood the gravity of the situation. I was calm during my first pregnancy, but I had mental and emotional difficulties after the delivery. My erratic behavior was thought to be linked to the problems of childbirth and new motherhood, and I recovered within a couple of weeks. The official diagnosis came later when my children were 5 and 3 years old.

My thoughts now are that it is absolutely possible to raise a family when managing a serious mental health condition, but one needs caregiver help when one is unwell, and a stable and supportive home environment to recover. Also, it is really important to build a bond with your children when you are well so that the children are happy, secure, and confident. My boys and I spend a lot of time together on a daily basis, which is a great source of comfort, security, and joy for all of us, and we are open about my condition.

Q. The memoir is not just about your journey but also includes brutally honest accounts of those who care for you. It shows how they processed and responded to your condition. How did you get them to share their stories? Did you have any guidelines on what they could or could not say?

A. There were no guidelines, I shared the questions with my family, and they responded over email or we spoke in person, or both, whatever they were comfortable with. I wanted to write this book as far back as 2015, and my family was initially not sure I would be able to pull it off, as I wasn’t as stable then as I am now. I think when they saw that I was able to re-visit the past without it triggering a mood episode, then they shared their thoughts more freely.

Q. A lot of Chemical Khichdi’s second half deals with existential, social, and personal suffering and struggling. It reads like a universal condition, and not a specific mental illness. How, then, does one distinguish when it becomes a matter of mental health?

A. Thanks for recognizing how universal these issues are. I feel existential, social, and personal suffering and struggling results in a mental health condition when it triggers a chemical imbalance. If I don’t sleep properly for five nights in a row, then it’s very likely I will become hypomanic and eventually manic. But what’s keeping me up for five nights in a row is a psychological issue. If these triggers result in behaviour that is very different from one’s ‘normal’ behavior, then it is an indication that there could be a mental health condition.

Not everyone has an underlying mental health condition, so even if they experience the same amount of sleeplessness, due to psychosocial triggers, it may not result in the same kind of behavioral change. There may be other impacts — for example, on physical health.

Q. One way to heal, you say, is to understand the mind-versus-intellect binary, i.e. know that the human mind has a rational and an irrational side. One side’s vicious emotions need to be conquered by the other, you suggest. But isn’t it this division that’s the root of the problem? Don’t you think it’s because we are conditioned to think that some thoughts are bad and should be suppressed that is why they come to haunt us?

A. I don’t think I’m trying to say that any thoughts should be suppressed or conquered. I think what I’m trying to point out is whether we choose to react to thoughts that are more indiscriminate, irrational, or impulsive versus thoughts that are more rational and discriminate. I have had all sorts of crazy thoughts during my mood swings as I’ve described in my book. But I am not judgmental of them or suppressing them. I know they exist, but I’m learning not to react to them.

I’ve shared an example of dealing with anger in the book. We all get angry and frustrated from time to time. The question is — how do we react to that feeling of anger? With mind or intellect? If we can step back from the anger with a sense of detachment, then we are attending to the emotion without suppressing it. We are applying intellect, not mind. The mind-body-intellect distinction actually allows both sets of thoughts and emotions to exist, with the possibility of choice on how to respond.

Q. Empathy requires one to be non-judgmental. The term has gained currency of late and you also practice it actively. But what does it really mean to be non-judgmental?

A. In my experience, being non-judgemental requires the ability to listen deeply. It’s important to be physically located in a place where the speaker feels completely comfortable and can share their story, whether in person, online, or over the phone. As the word suggests, it means withholding judgment of whether the speaker is right or wrong, and offering advice on the situation itself, rather than assessing the speaker’s action or thoughts. It’s important to react in a way that the advice is about the speaker and not the listener. For example, in the past, I’ve emptied my thoughts and emotions with a friend, and they’ve come back with, “Oh yes, I’m going through something similar.” It’s emphatic, but I would prefer a response that is more oriented towards me, such as, “I get it, that’s tough.”

Q. At one point in Chemical Khichdi, you write, “We are all in the same storm but not all in the same boat.” Could you elaborate a little more on it?

A. This was a phrase that was popular in the pandemic, recognising that while everyone was in lockdown, and thus in the same storm, some people were lucky enough to sail in luxurious yachts while others were struggling to stay afloat in tiny dinghies. A reflection of the inequalities of life, really.

Read other pieces by Sneha Bengani here.

First Published: Aug 12, 2022 7:08 PM IST

Check out our in-depth Market Coverage, Business News & get real-time Stock Market Updates on CNBC-TV18. Also, Watch our channels CNBC-TV18, CNBC Awaaz and CNBC Bajar Live on-the-go!

2024 Lok Sabha Election | Which way the wind blows in the second phase

Apr 26, 2024 6:09 PM

Election Commission registers case against BJP's Tejasvi Surya for alleged violation of poll code

Apr 26, 2024 5:08 PM

2024 Lok Sabha Elections | Why Kerala is in focus as the second phase begins to vote

Apr 26, 2024 9:33 AM

Bengaluru Rural Lok Sabha election: Over 60% voter turnout recorded by 5 pm

Apr 26, 2024 9:11 AM