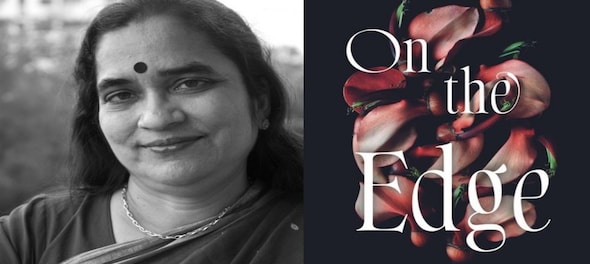

Novelist, teacher, and translator, Ruth Vanita has been a prominent voice focusing on same-sex desire, attraction, and love in Indian literature.

The author of several books, including Memory of Light; Love's Rite: Same-Sex Marriages in Modern India (2005); Gender, Sex and the City: Urdu Rekhti Poetry in India 1780-1870 (2012); and Dancing with the Nation: Courtesans in Bombay Cinema (2017), she is the co-editor of Same-Sex Love in India: A Literary History, and has notably translated many Hindi and Urdu works of fiction and poetry to English, most famously Chocolate: Stories on Male-Male Desire by Pandey Bechan Sharma 'Ugra' (2008).

Her new anthology, On The Edge, a is landmark collection of 16 short stories and excerpts from Hindi novels that explore same-sex love, either covertly or explicitly, that she has translated to English. Some of the inclusions are by popular giants such as Premchand and Geetanjali Shree. But On The Edge goes beyond and also indulges in forgotten gems by writers such as Asha Sahay, Ugra, Rajkamal Chaudhuri, Sara Rai, and Rajendra Yadav.

Here, the 67-year-old scholar discusses the anthology, the joy and difficulties of translation, what she thinks of the depiction of same-sex desire in Hindi films, the recent Supreme Court verdict, and how Hindi literature is opening up to homosexuality.

What got you to bring together this anthology?

A century had passed since Pandey Bechan Sharma Ugra’s story Chocolate gave rise to the first public debate on homosexuality in modern India. I thought it would be useful to see how Hindi fiction on the topic had evolved and to make this fiction available to those who do not read Hindi.

How did you decide which stories and writers to include?

I was familiar with some of the 16 stories that I finally translated, such as Geetanjali Shree’s Tirohit and Pankaj Bisht’s Pankhwali Naav. I had heard of others, such as Asha Sahay’s forgotten 1947 novel Ekakini. I spent months searching for it and finally found it online in a library. I also asked current writers to send me stories on this topic. I read several and selected some, by writers such as Akanksha Pare and Shubham Negi.

Why the title On the Edge?

It is my translation of the title of Sara Rai’s story, Kagaar Par, which appears in the book. Many of the characters in these stories find themselves on the edge of something – discovering themselves, telling others about their lives, committing suicide, or finding happy love.

Which of the 16 writers that you’ve featured in the anthology were the most difficult to translate and why?

Vijaydan Detha’s story was difficult to translate because of its beautiful lyricism which cannot be fully reproduced in English. Also, Shobhna Bhutani Siddique’s Lab-ba Lab, because of its racy colloquial language. Even the title contains an untranslatable pun. It means ‘Lip to Lip’ but also ‘Full to the Brim’.

What are your cardinal rules of translation?

I try to be as faithful as possible to the original while providing the reader with a smooth and seamless reading experience. My purpose is not to constantly remind the reader that this is a translation but to give the reader something close to the pleasure I derived from reading the original.

One myth about translators and translations that you’re tired of hearing?

That a translation is as good as the original. It almost never is.

How do you find the depiction of same-sex desire in Hindi films?

Hindi films were always unique in the way they depicted same-sex relationships, especially between men, as romantic friendships that are exclusive and often primary. Dosti (1969), Namak Haraam (1973), and Anand (1971) are a few examples of such films.

Even when not exclusive, the two male friends share everything, and live or die for each other, as the famous Sholay song says, ‘Meri jaan teri jaan / Aisa apnar pyaar/…Marna jeena saath hai’. Just as there were famous male-female pairings, there were famous male-male pairings, one of which fans called Shashitabh. After gay identities became more visible, some filmmakers grew wary of depicting intense and close friendships so they have three or four friends instead of two and ensure that all have girlfriends such as in 3 Idiots (2009) and Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara (2011).

The upside is that several wonderful films are now being made. Dedh Ishqiya (2014) is a lovely example; it contains clever allusions to Ismat Chugtai’s short story Lihaaf and Fire (1996). I often say that Shubh Mangal Zyada Saavdhan (2014) is the film I had been waiting for all my life. It acknowledges the way it is possible to read earlier films – with the famous Sholay motorbike song and also the song Admi hun admi se pyar karta hun from Pehchan (1970) which the gay character Pinku (played by Anupam Kher) in Mast Kalandar (1991), cheerfully sang to himself.

What do you think would be the social and cultural impact of the Supreme Court not granting legal recognition to same-sex marriages in its recent verdict?

In Shubh Mangal Zyada Saavdhan, when the male couple walks around the fire, Ayushmaan Khurrana’s character says to the spectators, "Watch this. You will see many more such weddings in the future." The first reported same-sex wedding by Hindu rites in India was that of policewomen Leela Namdeo and Urmila Srivastava in 1987. My book, Love’s Rite: Same-Sex Marriages in Modern India, lists many such weddings that happened in the 1980s and 1990s, a time when same-sex marriage was not legal anywhere in the world. The number of such weddings has increased exponentially in the 21st century and will continue to increase.

The courts and the governments can treat us as second-class citizens and deny us legal rights but they cannot stop same-sex marriages. As the Supreme Court judgment acknowledges, marriage was outside the purview of the state for millennia. All that marriage requires is two adult consenting partners. For many years, Jewish and Quaker marriages were not legally recognised in England. But Jews and Quakers did get married. Their marriages were valid despite the government's refusal to give them legal rights, and so are ours. Now our marriages are much more widely visible in India and people are getting used to the idea and seeing that society and culture are not destroyed by same-sex marriage, whether in the 34 countries that have legalised them or in countries like India that have not.

The anthology traces 100 years of Hindi fiction on same-sex desire. However, even after a century, such stories are few and far between. What can be done to remedy this?

There is much more fiction on the subject in English but gradually more is emerging in Indian languages too. Publishers are now not only willing but eager to publish on the subject in most languages. My novel Pariyon ke Beech (my Hindi transcreation of my English novel Memory of Light) was accepted by Rajkamal as soon as I offered it to them, and several novels and short story collections have appeared. Hindi magazines are also publishing many stories.

(Edited by : Vijay Anand)

First Published: Oct 23, 2023 8:36 PM IST

Check out our in-depth Market Coverage, Business News & get real-time Stock Market Updates on CNBC-TV18. Also, Watch our channels CNBC-TV18, CNBC Awaaz and CNBC Bajar Live on-the-go!