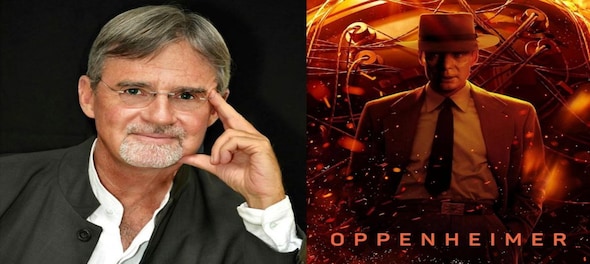

Encountering Kai Bird, the co-author of ‘American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer,’ the groundbreaking 2005 biography of the Father of the Atomic Bomb, at the recently concluded Jaipur Literature Festival was a delightful surprise.

I half-feared that the 72-year-old Pulitzer winner might be haughty and terse like several other big-ticket literary superstars I met this year. To my great relief and joy, he was anything but. It was because of his geniality and willingness to talk that I could steer our conversation in a myriad directions.

The result is a rich, detailed discussion about the troubled, complicated man that was Oppenheimer. Bird’s experience of committing his extraordinary life to paper, his reaction to the book being adapted to a blockbuster Christopher Nolan film, and why he thinks we are living in a dangerous world balanced on the precipice of Armageddon.

In this exclusive interview, Bird also talks about the imminent threat of nuclear terrorism, what made Oppenheimer a brilliant quantum physicist, why biographies should be taken seriously, how most wars are accidents, and how we can best navigate through the atomic age.

You've spent some part of your young life in India. What are your favourite memories from here?

Yes, I spent two years in high school at Kodaikanal in the Palani Hills and it's a beautiful area. I remember going on long hikes and rowing on the lake. It was an adventure. I travelled all over India later as a journalist. Sometimes in the general coach. That's an experience like few others. I love India, being back here, the food, and wearing Nehru jackets.

What is it about powerful figures that draw you towards them?

I've always written biographies of people like John McCloy, a powerful Wall Street lawyer, George Bundy, who was a major architect of the war in Vietnam, and Oppenheimer. I'm interested in how power works, especially in America. Because I grew up in the Middle East, in India, I was sort of a stranger to America when I went back to live there in college. I didn't understand it so in a way biography is my way to understand America.

Why Oppenheimer?

I always understood that he was an important figure. The father of the atomic bomb. He gave us the atomic age, which we're still living with. I wrote about him in my first two biographies a little bit because he was friends with John McCloy and George Bundy. But the real reason I ended up writing Oppenheimer’s biography is that my friend Martin Sherwin signed a contract in 1980 to do it. And then 20 years later, he came to me and said he would like me to join him on his project. He hadn't started to write yet. He was still researching.

What does it take to write about a man as powerful, important, and in the public eye as Oppenheimer? What was the process like? How long did it take?

Well, Marty spent 25 years on it and I spent only the last five years. By that time Marty had collected 50,000 pages of archival documents, 7,000 pages alone of FBI documents. He'd done 150 interviews, all neatly transcribed, of Oppenheimer's students, colleagues, and relatives. It was a very rich collection of sources. The writing flowed because there were so many stories to tell. But it still took five years for us to write and publish the book.

What was it like winning the Pulitzer for it? Did it change things for you dramatically?

Many of these prizes and awards are very subjective. A lot of it is due to chance. I've been on prize committees and there may be three people on the committee and we all have different views. So it's very subjective.

But when Oppenheimer was published in 2005, it got terrific reviews everywhere but it didn't sell very well. It sold modestly. I told Marty that I thought it might be a contender for the Pulitzer Prize. And he said, oh, you're dreaming. He was much more sceptical. But when we won it in 2006, he was very pleased.

It's the only prize in America that sort of changes the life of a book. It immediately sells many more copies. The book gets a lot more attention. It's going to be in print for a long time. And it allowed me to do the things that I wouldn't have been able to do otherwise. Like my next book, I decided I wanted to write a memoir about growing up in the Middle East and India. And they never would have given me a book contract without the Pulitzer.

Any startling or unexpected discovery about Oppenheimer or America in general while you were working on the book?

Well, I had known what had happened to Oppenheimer. But I was unaware of how humiliated he was. What a sort of black mark this was on the country's history. It destroyed him. Up until 1954, he had been a famous man, a hero, and a respected scientist. And then after 1954, he was a pariah. He was disinvited from giving university lectures. He was suspected of being a spy. His son was taunted in school over his father being a communist.

So that summer, after the April trial, he took his family on a sailing trip to the Caribbean. He discovered St. John and fell in love with it and the Virgin Islands. He bought a piece of property right on the beach and built a very spartan cabin. Very simple. And he spent the rest of his life, every year, four to five months, just living in this tiny cottage, walking the beach alone. It was a very sad ending to an interesting scientific life. And so that was kind of shocking to me.

According to you, what's the one most misunderstood thing about Oppenheimer, the man?

I think people have a misconception about scientists. They think of Oppenheimer only in simplistic terms as the father of the atomic bomb, a quantum physicist. But to be a good scientist, you have to be also a good human being. You have to be curious about the physical world around you. And it also helps if you are in love with literature and poetry, because that teaches you to ask the right questions, scientifically.

Quantum theory is complicated for human beings to understand because it explains the world, atoms, electrons, and how things move in that small world. But the rules don't make sense. They're not common-sensical. They're absurd. But they work. And Oppenheimer was able to be a good quantum physicist because he was a humanist. He could hear the music, he could understand the possibilities.

People don't understand science. We live in a world surrounded by computers and technology and we just use it, but we don't understand how it works or how it's changed our lives. And we don't understand the scientific mind, the process of experimental examination. This was proved most recently during the pandemic when public health officials were desperately trying to understand what was happening, what was the nature of this virus and how to combat it. And most people around the world sort of fell into either conspiracy theories or ignorant practices. So it's clear we are surrounded by science, but most of our people don't understand science at all.

After Christopher Nolan's film, there's a massive renewed interest in Oppenheimer. How satisfied or happy are you with the way it turned out?

The movie, I think, is brilliant art. It's a cinematic spectacle. It's very good entertainment. But it's a miracle to me that it's also historically accurate. It is based on the book. I recognise whole lines and paragraphs that come straight out of the book. It captures Oppenheimer's personality, politics, love affairs, and marriage. It tells the important parts of his life.

It doesn't address his childhood or what happened to him after the trial. The St. John Island thing is completely out of there. But the important parts of his life are reflected in the film, and most importantly, the trial, which is the critical story about his life. The fact that he built this weapon. But what makes his life interesting is that he was destroyed nine years after being celebrated. And why.

It's surprising to me that so many young people like you have gone to see the film. What did you know about Oppenheimer before? But it was still of interest.

What advice do you have for journalists who want to write books of worth?

I would recommend writing a biography. That's a good way to start. I'm sure there are many worthy subjects around Indian politics or Bollywood. But journalists should understand that biography is not about celebrity. It's about telling the complicated life story of any human being.

So I could decide to write your biography. And I could make it very interesting. I could find your high school friends, interview your relatives, and look at the newspapers and the stories that were published around the time you were born to recreate the world that you lived in. It's a very worthy historical vehicle for conveying both history and stories about the human condition. So biography should be taken seriously.

It's very difficult. It's the most arduous scholarship because you need to have a footnote for every quote so that you establish a bond, a trust with your reader. You need to be able to persuade them that even if it's your story about Jimmy Carter, the choices that you’ve made in it are good ones and that they're based on certain sources that they can go and check.

Any valuable lessons that the world today can learn from the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki?

Absolutely. The atomic age started more than 75 years ago and we've become complacent. People say, oh, 75 years, we haven't had another Hiroshima or Nagasaki. True, but, 75 years is just a drop in the ocean of time. It is. Something terrible could happen tomorrow or 500 years from now and we should be listening to what Oppenheimer said about the bomb in 1945, three months after Hiroshima.

He said you may think that this weapon was very expensive because we spent $2 billion on it. It is very cheap, and any country, however poor, anywhere in the world that wants to build these weapons will be able to do so. There are no secrets and we all know how to do it now. You may think that these are weapons of defense but actually, they are weapons for aggressors. They are weapons of terror.

He went on to say that he learned after Hiroshima that they were used on an already defeated enemy. Two years later, he warned about nuclear terrorism, about dirty bombs, and we haven't listened to him. Instead, America went on a binge of building thousands of these weapons thinking that they provided deterrence.

But look at what we have today in the Ukraine war. Putin has been threatening to use tactical nuclear weapons if he is faced with conventional defeat. And we have a war in the Middle East now. We have India armed with nuclear weapons and Pakistan and they could someday have a war on Kashmir. Things could easily get out of control. Most wars are accidents. They happen because of unintended consequences and misunderstandings of your opponent's intentions. And so, because they exist, they may someday be used again.

Oppenheimer never regretted or apologied for Hiroshima and Nagasaki because he thought he was in a race with the Nazis to build these. But he spent the rest of his life trying to warn people that we need to control this technology. We need to ban the bomb but use nuclear energy, have an international atomic authority that has sovereign rights to go anywhere, inspect any laboratory, any factory, and prohibit the building of these weapons. This is a plan that could work. But it hasn't happened yet.

First Published: Feb 20, 2024 1:27 PM IST

Check out our in-depth Market Coverage, Business News & get real-time Stock Market Updates on CNBC-TV18. Also, Watch our channels CNBC-TV18, CNBC Awaaz and CNBC Bajar Live on-the-go!

Feroze Gandhi to Rahul Gandhi: Rae Bareli's tryst with Congress

May 3, 2024 11:36 AM

Rahul Gandhi to contest from Raebareli, close aide KL Sharma from Amethi

May 3, 2024 8:39 AM

BJP's Hindi heartland dominance faces test in phase 3 polls

May 2, 2024 9:14 PM