A professor of history at Birkbeck, University of London, a fellow of the British Academy, and the author of several pioneering books, Joanna Bourke has spent the last 30 years exploring the histories of military medicine, modern warfare, psychology and psychiatry, emotions, and rape.

Some of her most notable works include The Story of Pain: From Prayer to Painkillers (2014), Fear: A Cultural History (2006), and What It Means to Be Human (2011). Her books have been translated into Chinese, Russian, Spanish, Catalan, Italian, Portuguese, Czech, Turkish, and Greek.

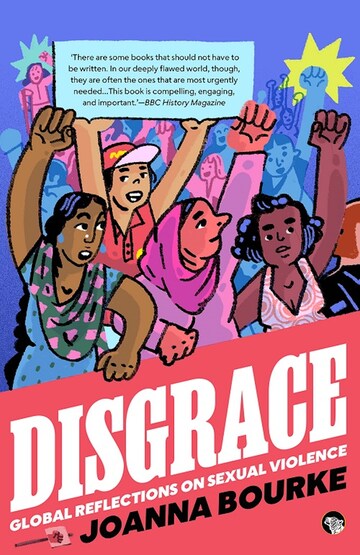

A New Zealander by birth, she is also the chief investigator for an interdisciplinary project called SHaME (Sexual Harms and Medical Encounters), which investigates sexual violence from an international perspective, specifically through the lens of medicine and psychiatry. Her new book, Disgrace: Global Reflections on Sexual Violence (published by Speaking Tiger Books), is the first under this project.

In this exclusive interview, the British academic-historian delves into how it took her a decade to write this book, the ethical dilemmas of writing a global history as expansive as Disgrace, rape myths, why we should all be involved in the anti-rape movement, the emotional cost of working on sexual violence, and what keeps her hopeful despite it all.

The title of the book, Disgrace, is so hard-hitting. How did you arrive at it?

The book was born out of a huge sense of anger about how people who have experienced sexual violence are treated. Many of my friends and colleagues have survived sexual assault, yet they are made to feel humiliated. Why do they feel disgraced, shamed, and dishonoured? Shouldn’t the people who carry out acts of sexual violence feel disgraced?

It is disgraceful that sexual violence remains such a problem. It is a disgrace that some people minimise the sexual harm inflicted on people of different genders, sexualities, races, ethnicities, classes, castes, religions, ages, generations, body types, (dis)-abilities, and so on. It is disgraceful that levels of violence are rising while convictions are declining.

In the last few decades, there have been incredible feminist campaigns against sexual violence; teachers have revised the content of sex education classes; politicians have passed progressive legislation; legal experts have improved the ways they treat people complaining of rape in courtrooms; the MeToo movement has flourished – but, throughout the world, sexual violence continues to flourish.

I live in Britain and Greece: in those countries, one in five women and one in 12 men will be sexually assaulted in their lifetime. Rates of abuse are significantly higher in some countries (particularly those experiencing armed conflict) and also higher for certain groups (particularly people belonging to minoritized communities). This is disgraceful.

It is so thoroughly, and meticulously researched. How long did take to investigate and write it?

The book has taken 10 years to research and write. Of course, I have done other things in that decade, including teaching at Birkbeck, University of London, and writing other books and articles. But Disgrace has always been a top priority. I have learned so much over the decade of writing the book.

What was the most difficult aspect of writing Disgrace?

Without a doubt, the ethical dilemmas of writing a global history have been the most difficult. I am a white, economically secure, urban woman. My worldview has been fundamentally shaped by a childhood in New Zealand, Zambia, Solomon Islands, and (most important in terms of my political orientation) Haiti. I currently live in Britain and Greece, where I am fortunate to be surrounded by a community of male, female, and non-binary friends who are emotionally supportive. This puts me in a very privileged position.

The main dilemma, then, is: How can I tell a global story about sexual violence as it affects marginalised people in countries distant from my own? Is there a risk of appropriating their experiences and life stories? Terror is always local and unevenly distributed: how can I do justice to such diversity and intersectionalities? How can I ensure that survivors of sexual abuse are placed centre stage? In writing about such terrifying experiences, how can I avoid frightening my readers or stripping the people I am writing about of agency? Is there a risk of voyeurism? Might I inadvertently re-violate people who have already experienced harm? Despite a decade of work, I don’t think I am able to answer all of these questions, but I continue to try.

In the introduction, you write that rape is culturally constructed. How do you mean?

One of the most striking things about investigating sexual violence is how ideas about it change so dramatically over time and between different social, economic, and political communities. My book spans the period from the 19th century to the present. As I state in Disgrace, drawing comparisons between such different time periods and locations is challenging.

For example, the women violated by the Red Army soldiers in 1945 cannot realistically be compared to Dalit women raped by men of ‘higher’ castes today; 19th-century peasant women in Ireland who were abducted as a way of forcing marriage have little in common with date-raped high-school students in 20th-century America; French wives who acquiesce to sexual intercourse with their husbands as the ‘easier option’ bear no resemblance to ‘bush wives’ in Sierra Leone; it matters if you are a boy, man, or non-binary person; it makes a difference if the attacker wields a machete or raises the threat of an unsigned employment contract. In each of these examples, sexual violence is understood differently. However, in each instance, sexual violence is ‘culturally constructed’.

In a country where sexual violence is as alarmingly common as in India, several landmark cases have rocked the nation. What made you specifically discuss Bilkis Bano’s in the special preface to the Indian edition?

Every year, over 30,000 girls and women in India are raped; this means that there are 49 victims of sexual abuse every hour. I have long been inspired by feminists in India: their political labour has been important in bringing the world’s attention not only to important facets of sexual violence but also to ways of resisting. This is why Indian examples appear throughout my book, especially in the context of partition and post-1980s activism against violence in the home, and against transgender individuals and caste minorities.

The preface for the Indian edition starts with the 2022 release from prison of the 11 men convicted to life imprisonment for the rape of Bilkis Bano because it occurred shortly before my book was published. It is a reminder that the struggle for justice is an ongoing one.

One startling discovery/insight that you stumbled upon while working on this book?

The most startling thing for me is just how embedded ‘rape myths’ still are in societies around the world. I continue to be shocked by the casual sense of entitlement that some people assume over other people’s bodies. This is particularly common among boys and men, for whom ‘access’ to the sexed bodies of their partners or girlfriends is often assumed (and, for most of history, has been allowed by law and convention).

Understanding the history of this sense of entitlement is crucial. For centuries, men have made the rules, particularly in terms of law and policing. So-called ‘rape myths’ permeate society and largely determine what is considered ‘real rape’. One of the most pernicious is the myth that ‘you can’t rape a resisting woman’. In other words, if a woman does not want sexual intercourse, she will be capable of fighting off any assailant.

In medical and legal textbooks published in India and the UK, this is sometimes summarised as ‘It is impossible to sheath a sword into a vibrating scabbard’ – a horrid phrase in which the penis is coded as a weapon, the vagina as a sheath that simply by ‘vibrating’ (!) could always stop penetration. It is important to note that there is a class/caste element to this myth. More privileged women who allege rape are assumed to be more ‘delicate’ than their poorer sisters, so their inability to fight off an attacker could be taken more seriously.

But there are other ‘rape myths’ that continue to be heard and have a huge impact not only on justice systems but also on how survivors, as well as perpetrators of sexual violence, conceptualise these acts. One of the other harmful myths is ‘no wound, no rape’: if a victim can’t show a physical wound, then the assault either didn’t happen or its seriousness can be minimised. This myth is tied to the one about ‘stranger rape’ being the only ‘true’ kind. It is a myth that appears most strongly in the media, which has a huge impact on what people think is ‘real rape’.

A lot has changed in the last decade (I am thinking especially of the fantastic British TV series by Michaela Coel, I May Destroy You), but is still the main way many people think about rape. This is also influenced by forensic science – especially when used in court – which encourages jurors to expect to see lesions and bruising. However, most victims of sexual assault don’t have wounds, and the DNA technologies are not perfect, so much of that evidence is also thrown out. In popular parlance, this is called the CSI effect, meaning you have to have forensic evidence for an assault to be judged as ‘real rape’. Again, in order to understand why these myths are so prevalent, we need to study their history.

How do you protect yourself from the emotional and mental toll of working on a subject as infuriating and overwhelming as gender-based sexual cruelty for as long as you have?

Working on violence can be emotionally draining. You are right: I have worked in this field for a very long time, so I try to encourage, nurture, and simply ‘look after’ people who are just beginning to think and work on sexual violence.

The most important thing is political optimism. We can change our world for the better! I keep harm-ignoring, violence-minimising, or rape-excusing people at a personal distance, preferring to surround myself with feminist friends and colleagues from all genders. I have discovered that so many people share my optimism and, although we may disagree about tactics and strategies, I always enjoy our discussions and debates. Crucially: I also ‘have a life’ apart from thinking and writing about violence – cooking, poetry, music, and laughter. I share these ‘good things’ with ‘good people’.

What is your secret behind such a prolific and illustrious writing and academic career?

Hard work! I am a bit of a workaholic, sorry to say. But I love what I do. I enjoy thinking about ‘big topics’; I revel in the research process; like most people, I find writing exhausting and I do hundreds of drafts, but, in the end, it is a thoroughly enjoyable process. I have also been a university professor for most of my life. Teaching is fulfilling. I teach at Birkbeck, which is the part of the University of London that holds classes in the evenings. This means that my students often work during the day. They bring very different skills and pieces of knowledge to the classroom – so are wonderful when ‘trying out’ ideas.

Three feminist readings that you think should be mandatory for everybody.

1.

Chandra Talpade Mohanty, Feminism without Borders: Decolonizing Theory, Practicing Solidarity (2003)

2. Judith Butler and Joan W. Scott (eds.), Feminists Theorize the Political (1992)

3. Estelle Freedman (ed.), The Essential Feminist Reader (2007)

But I would also recommend that people working in the field of sexual violence read poetry. I always get inspiration from Adrienne Rich, Audre Lorde, Wanda Coleman, and bell hooks.

In a world marred by such rampant violence, misogyny, and general systemic apathy, what keeps you hopeful?

I am always hopeful – mainly because I believe, firstly, that everyone wants love, respect, and friendship and we can harness those needs in working for a better world, and secondly, there are numerous strategies we can employ to create a rape-free world.

Of course, creating a world without abuse will require the political and social labour of each and every one of us. As I argue in the book, we all need to think: given my skills, location, community base, and politics, what is the most appropriate and most effective action I can take to make the world free of sexual violence? How can I make coalitions with other people who are fighting for a rape-free world?

This will include involving everyone – including boys and men. Although girls and women are the vast majority of people who are abused, boys and men are a large minority. It is in all of our interests to be involved in the anti-rape movement. We are all diminished when another person is sexually abused. We all have preferences, skills, and spheres of influence that we can exploit in our struggle to eradicate sexual violence in our communities.

My entire book provides examples of how people have resisted violence in the past while my last chapter hones in on positive steps that we can take in the future. And, yes, I am confident that it is possible to create worlds of safety, equality, and human flourishing.

(Edited by : Vijay Anand)

First Published: Oct 23, 2023 8:50 PM IST

Check out our in-depth Market Coverage, Business News & get real-time Stock Market Updates on CNBC-TV18. Also, Watch our channels CNBC-TV18, CNBC Awaaz and CNBC Bajar Live on-the-go!