After directing Hostages, the Hindi remake of the Israeli show of the same name for Disney+ Hotstar in 2019, and adapting Manu Joseph’s celebrated novel Serious Men for Netflix the next year, Sudhir Mishra has just rolled out another show.

Based on the 2015 Israeli television series Fauda, Tanaav is set in Kashmir and features Arbaaz Khan, Rajat Kapoor, Manav Vij, Shashank Arora, Danish Husain, and Ekta Kaul in key roles. Directed by Mishra and Sachin Mamta Krishn, it premiered on SonyLIV on November 11.

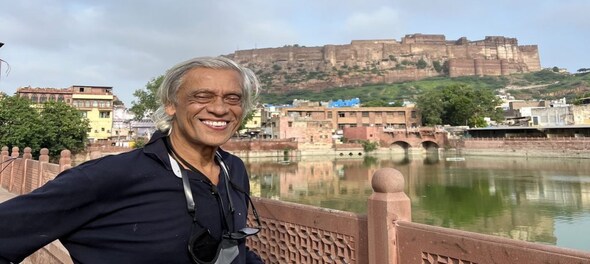

In this candid conversation, the 63-year-old filmmaker, known for helming movies such as Chameli (2004), Hazaaron Khwahishein Aisi (2005), and Inkaar (2013), talks at length about Tanaav, why he thinks Hindi film heroes don’t work with him, how the streaming explosion has given him a new lease of life, and what makes him want to continue making films for another 35 years.

Q. Why a story on Kashmir?

A. The idea of adapting Fauda came from Sameer Nair of Applause Entertainment. He contacted me because I have a sense of India more than most filmmakers. Some of us don’t read, write, travel, and interact to make films alone but we do it because it’s our proclivity. The story lent itself naturally to Kashmir but we had to reimagine it a bit. For instance, Fauda is about two countries, but Tanaav is about the conflict within the same country. Fauda is about two religions, but we didn’t want to make Tanaav about that. We have kept it kind of neutral.

It’s interesting because the original is also complex. It’s not so-and-so versus so-and-so. The first season will give you a good understanding of all that has been happening. There are wonderful female characters too who present the point of view of the women in Kashmir.

Q. The cast of Tanaav has some great actors but it has no stars. Was it a conscious choice?

A. Very conscious. And that’s the good thing about OTT—it allows you to make such choices. So when we say that Kabir (a character in the show) is from Kishtwar, you can cast a Punjabi like Manav Vij. For a character like Malik, you can cast Rajat Kapoor. If you want Kashmiri characters, you can cast MK Raina, Idris Malik, and Sumit Kaul. These faces talked, they speak to you; they seemed to be in sync with the landscape. We have tried to cast a lot of Kashmiris to make sure the show feels authentic.

Q. But don’t you think it’ll affect the way it will be received because we still are quite obsessed with stars?

A. It’s changing. There are three shows that are very successful in Indian OTT history. One is Sacred Games part 1, which has stars that were cast as actors. Then there are Scam 1992 and Pataal Lok, which have no stars. There is also Jamtara, Gullak, Tabbar, Panchayat.

The small screen is about stories, people, and skills. A lot of stars get away with the big screen because the screen helps them. It’s 70 mm, there’s Dolby sound, the spectacle of it all helps. But here you cannot escape the fact that you are not skilled. If you can’t perform, if you’re not an actor, you get caught out. The biggest of them have been. It’s not a medium for mannerisms. It’s not a platform for bad actors or bad writing. And good writing requires good actors.

Q. Your characters are mostly people living on the margins. What is it about them that speaks to you so much?

A. I like people who are frail and trying to handle the chaos of this world, find some kind of meaning, and wondering if there is any at all. That’s how most people are and which is why most male stars don’t work with me. They don’t like to portray frailty.

It’s how I am. I don’t try to analyse the reasons behind why I do what I do. I don’t know whether I find the story or the story finds me. I have no idea. I like to keep the mystery. When something speaks to me, I just flow with it. I’m not a technical person. You go to the right location, sit and listen, and it will tell you how to shoot it. It’s as much for me an act of listening and my major frustration is that I’m good enough, not talented enough, that I’m not Scorsese. I feel it every day, all the time.

Q. Even after being in films for 35 years?

A. I have no idea I have been here 35 years. I forget how I shoot; I suffer from amnesia. I could go on making films for the next 35 years. I’m quite in rhythm with the young, quite irreverent with them. I’m not scared of the young. Probably because I don’t have children. Most people get cowed down by their children. They say, daddy, you’re now passé. Nobody is telling me that.

Q. Though they are often social commentaries, your films are also deeply political. Do you think you can ever make a mainstream Bollywood film?

A. No. Some film of mine can become mainstream but if you are asking whether I can make a formulaic film, no. I have nothing against song and dance. That’s a style. If a film detaches itself from realism and says I want to be a musical, for instance, I have no problem. But let me make a musical my way. Every filmmaker, if you ask them, would give their left arm to make a musical. But in their own way.

Q. It would be fun to see a musical directed by you. Has no one approached you with it so far? Why haven’t you made one yet?

A. The film that gets made is the film that gets produced and producers slot you. Though a lot of people tell me that the music in my films is good. I’ve done Chameli and Hazaaron Khwahishein Aisi. People like their music a lot. But I don’t know if it’s mainstream. It belongs to a larger frame. Musicals also require bigger budgets, which require bigger stars. So you realise why I don’t make them. Bigger stars don’t like me.

Q. Why do you think so?

A. They don’t like me in the sense that because my male characters are frail and are trying to figure out their place in the world, they are wrong sometimes, and they compromise. Stars want to play strong even if it’s a bad guy they are playing.

Thankfully, that’s not always the case with female actors. I have just done a short film with Taapsee Pannu. It’s part of an anthology that Ketan Mehta, Hansal Mehta, Anubhav Sinha, and I are doing. I’ve also finished a feature called Afwaah with Nawazuddin Siddiqui and Bhumi Pednekar. Women are not afraid of being wrong or playing weak. You can do a more interesting trajectory with them.

I think it also has to do with the kind of films I make. I don’t think there are any heroes anyway. That’s my point of view in life. So I don’t know. It remains a mystery.

Q. The streaming revolution has made you more prolific than ever. You have never been busier.

A. Ya, suddenly they have discovered that I might have something in me. Streaming projects are not bound by the first weekend. The platform lets things grow, it’s not immediate. We have to step out of this immediacy, this what doesn’t work the first weekend doesn’t work at all kind of mindset.

The OTT audience is different from those who watch TV or go to the theatre. They are fussy and individualistic, they are not going to jump because I have made a film. They have their own schedules in life and are going to see it at their own time. That’s the nature of our audience. They may like your work, admire it, but they are not mad fans. We need more time for our films. For instance, Hazaaron Khwahishein Aisi took about five-six years of people seeing it on all sorts of platforms to become what it became.

Read other pieces by Sneha Bengani here.

Check out our in-depth Market Coverage, Business News & get real-time Stock Market Updates on CNBC-TV18. Also, Watch our channels CNBC-TV18, CNBC Awaaz and CNBC Bajar Live on-the-go!

Lok Sabha Election 2024: Issues raised by Prime Minister Modi have not resonated with people of Tamil Nadu, says Congress

Apr 19, 2024 11:38 PM

West Bengal Lok Sabha elections 2024: A look at Congress candidates

Apr 19, 2024 8:45 PM