Though all his writing is rooted in travel, reading Pico Iyer feels curiously meditative as one does when looking out the window of a moving vehicle on a quiet, solitary journey or when sitting cross-legged in a monastery washed in silence.

That’s high praise for a travel writer because it is easy to get lost in all the noise, the constant activity, the facts, and the descriptions when you’ve been to places as diverse, obscure, and transformative as Iyer has been. But he grounds his work in spirituality with such rare tenderness and insight that even his non-fiction has the sub-textual richness and the emotional gravitas of a novel.

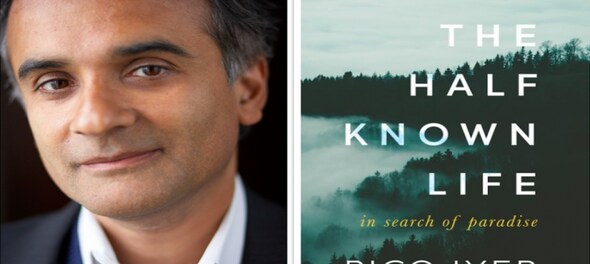

Here, the prolific Iyer discusses his latest book The Half Known Life, the fascinating interplay between his inner and outer worlds, why he’s never used a cell phone, the true meaning of finding your voice, how he avoids burnout, the time when he traveled to Antarctica, why he would not recommend his life to anyone else, and his idea of paradise.

Q. What got you to write The Half Known Life?

A. Living every moment in the uncertainty of the pandemic made me think that if uncertainty is our home, we need to make it as warm and comfortable a home as possible and to find what fulfillment and joy we can even within those very strict limits. And getting to spend months on end at home allowed me both to think about what my 48 years of constant travel had amounted to, and to write a single, pointed inquiry about looking for paradise in the heart of real life.

I do feel that, in the age of Information, we know less than we ever did, often, in part because we get so much at a distance or only through screens. And it’s harder than ever to sift the trivial from the essential, as well as the true from the false. Seeing everything through a small screen gives us little sense of the larger picture.

But I also, especially as I grow older, see how everything essential in our lives—falling in love, being hit by a virus, seeing one’s house burn down in a forest fire, being moved beyond words in the Himalayas—exists beyond our explanations. You could say this book is about traveling out from my ideas of the world, and my theories, into a real world that will always be richer and deeper, and more surprising than my ideas of it.

Q. What do you enjoy writing more—non-fiction or novels? Are your processes different for each?

A. I enjoy writing fiction more precisely because I don’t know how to do it. It’s like a journey into the dark and I have no sense of where I’ll end up. And that darkness belongs both to the subconscious, which is really what is fashioning the work, and to the darkness of working without an outline (or hoping you will bump off the track of that outline into something unknown).

With non-fiction, I have a clearer sense of where I’m going, if only because I’ve done it much more often. This means that I can offer more to the reader in non-fiction (since if she loves novels, she can turn to Proust or Melville or Arundhati Roy with much more delight). And also means that I have a much richer adventure writing fiction, but see no point in inflicting my imperfect efforts on the reader.

In terms of process, fiction is usually only as strong as its grounding in precision and fact of some kind; and non-fiction comes to life only when it deploys the basic tools of non-fiction—story-telling, character and dialogue. I try more and more to write non-fiction as if it were fiction, coming from a mysterious source and drawing on memories, intimations, and imaginings more than on notes. When I published a book on Graham Greene some years ago, I deliberately took out the sub-title, so nobody could tell how much it was fiction, how much non-fiction; like the best things in life—such as poetry—it aspired to shimmer in the space between the two,

Q. Most of your work is a curious inquiry of the inner and outer worlds and the space between them. Could you shed some light on how each of your worlds informs and nourishes the other and the fascinating play between the two?

A. Thank you for this question, and you’re absolutely right: I very much think of my work as an “inquiry” and I work hard, as in The Half Known Life, to balance the external details of Iran, North Korea, Jerusalem—and Kashmir, Varanasi, Ladakh—with the inner life, I get from spending much of my life in monasteries and from hanging out with Melville, Emily Dickinson, the works of Thomas Merton.

When I was a boy, I thought that the two things I needed to do were to understand the world and to try to spend time with the inner landscape. So I worked to enjoy the chance to travel, everywhere from Tibet to Easter Island, while also spending much of my time on retreat and trying to ensure that I wasn’t simply hostage to the external world. All of us, I think, are permanently trying to balance these two: if we’re too caught up in the external world, we can’t remember what’s important or chart a direction in life. And if we’re too rooted in the internal world, we can lose contact with what’s real, and not just in our heads.

I always remember Meister Eckhart, the great German mystic, saying that if the inner work is strong, the outer can never be puny. Which refers to our relationships, our careers, and our thoughts. And these days the external world is so much with us that it’s easy to lose sight of what is much more essential. In this book, I take the poems of Emily Dickinson with me to the mystical Japanese mountain known as Koyasan to ensure that I’m not just taking in surfaces—and also because, though so many have written about Koyasan, and so many have written about Emily Dickinson, few have thought to bring the two together and see how inner world can illuminate outer, and outer world can expand inner.

Q. How do you continue to be so prolific?

A. Probably in the worst possible ways. I live in a rented, two-room apartment in the middle of a boring suburb in Japan, and I don’t speak much Japanese. I’ve never used a cell phone and I don’t have a car or bicycle. And I really find that when I succumb to distraction—watching TV, reading the news, making chit-chat—I feel cut up and hopeless; as soon as I look up and out, or take a walk around the neighborhood, I feel opened up and flooded with hope.

So my life is not one I would recommend to anyone else. But I find I am happiest when I am most deeply absorbed in something, and nothing so consumes me as the challenges at the desk. Whether they involve writing a 200-word piece on a place I’ve just visited or putting together a full book.

I don’t want quantity to eclipse quality, and many of the writers I cherish most didn’t (or don’t) write much at all. But selfishly I love to write because it’s the hobby (and discipline) that affords me the greatest delight and seems the richest adventure. Roger Federer didn’t want to give up tennis, Tom Brady in the U.S. refused to retire from American football. I feel the same way about my life at the desk: it’s all I know how to do, and the biggest high I’ve found.

Q. Have you ever felt stuck in your writing career of over 40 years? What do you do to avoid burnout? How do you recover from them?

A. To be honest, I haven’t felt stuck, which may not be a good thing. Writing shouldn’t come too easily. But because I’m involved, every day, in a variety of projects, if I’m tired or distracted one day, I’ll give myself to some relatively mindless pursuit—fact-checking or typing up something I’ve written (since I write everything by hand). Knowing that the next day I’ll probably have more words flooding through me than I know what to do with. And if I’m not in the right state to give myself to a long and thoughtful project, I’ll write something that needs to be much quicker and closer to the surface.

In terms of burnout, I feel lucky because I’m always taking on different kinds of projects and trying to look around the next corner. If I’ve just completed a long book on the Dalai Lama, I’ll give myself to a book on Graham Greene, which is likely to exhilarate, surprise and challenge as much as a journey to a foreign country. And if I’ve just completed that, I’ll write a short book on stillness and then two contradictory books on Japan.

Plus, I do spend half my day far from my desk. Since I wake up early, I usually conclude my working day by 2.00 p.m. And then I can give myself to games of ping-pong, trips to the health club, walks around the local park. To long conversations with my wife, to movies, to seeing and visiting friends. And it’s often when I’m walking the treadmill at the health club, or watching a film, that something stirs in my subconscious and I’m excited to sense that I have something fresh and new to offer when I go back to the desk the next day.

Q. What’s been your most transformative travel experience in recent years?

A. I’m glad you asked this because I haven’t had much of a chance to talk about it. Just as the pandemic was dawning, I found myself sailing around Antarctica (payment for a job I had the year before). I’m mostly an urban creature, so I hadn’t been excited about the trip as many of my friends would be. But Antarctica silenced and humbled me at every moment.

The thousand shades of silver as far as I could see. The whales breaching near the prow of our shop and the penguins busily going about their lives two feet away from me and my wife. Silent mornings sailing amidst five-story icebergs that were turquoise and emerald and aquamarine. It was a lesson in sublimity and scale, in wild majesty. It was also a lesson in how much we’re using the planet and destroying it; like the best trips, it sent me home with difficult questions about how we can be responsible for and to the environment we’re so greedily devastating.

And this past year, I found myself in Zanzibar, the kind of destination I’d dreamed of as a little boy but never imagined I might see in life. The world is truly inexhaustible.

Q. Two valuable learnings that you’d like to share with people wanting to make a career in travel writing?

A. Be as focused as you can and try to find what you can see—and therefore say—that most of the rest of us cannot. Every day thousands of people go to the Taj Mahal, and each person registers something different: the gardens, the inscriptions, the coral, and the lapis lazuli. Every single one of us, because of our background, our experiences, and our passions, is sensitive and wide-awake to aspects that most of the people around us sleepwalk past.

That’s what is meant by “finding your voice”: finding your own special set of eyes. Being aware of the things you register that your friends never would. It often takes work to uncover what is particular to you, but every human being is in possession of a special key of this kind, and that’s what she has to offer when she writes, or when she describes a destination to friends and strangers.

Q. Has the way you see travel changed post COVID-19?

A. The main thing, in the short-term, is that travel has become so chaotic, as millions of us try to cram two years of lockdown dreams into two weeks or to make up for the lost time. This will no doubt calm down in time, but for now, it’s made traveling quite difficult. Two two-hour flights last April in the U.S. took me 27 hours to complete.

The pandemic for me showed how many wonders there are to be found close to home; when I started taking walks along the road behind my mother’s house—as I hadn’t done in the fifty years she’d been living there—I found peacocks and quiet and natural beauty as transformative as anything I’d encountered across the globe. While not damaging the environment as much as I might otherwise, or my jetlagged system (perhaps never meant for crossing 17 time zones in a day).

So maybe the doors opened by lockdown and the crazy mayhem in airports these past few months will move more and more of us to travel in different ways, and ways more sensitive to the environment.

Q. What’s the one thing that you really look forward to when you visit a new place?

A. Surprise. I begin my new book by writing about Iran because I’d studied that country, written fiction and non-fiction about it, and read up on its history for 30 years before I arrived. And within four hours of arrival, I saw that I didn’t know a thing.

There were French boutiques next to the small mosque in my hotel lobby. The women all around were dressed in the latest fashions under their hijabs. The announcements on the local planes were delivered in impeccable English. CNN was on the TV in my hotel room.

Iran was the most sophisticated and richest place I’ve ever seen, whose sense of veils and intricate aesthetics, whose blue-tiled mosques and luxurious gardens lived up to every expectation. But the great gift it offered me was unexpectedness and the bracing sense that I could never anticipate what I would encounter the next moment.

Q. In all your many travels, have you found your idea of paradise? Do you think such a place exists?

A. I only trust a paradise that’s durable, that’s democratic, and can exist within a very real world that includes suffering and difficulty, and death. Here in Japan, when one enters a temple, one often sees, on the ground at the entrance, the words “Look Beneath Your Feet.”

So I think Paradise—or at least contentment and calm—can be found in many places; I feature His Holiness the Dalai Lama in many places in this book because his life has involved more challenge and often loss than that of anyone I know, and nobody is more famous for his broad smile, his infectious laugh and his indomitable sense of confidence.

As you know, I end my book in Varanasi. The first time I visited, I didn’t know what to make of all the clamor, the chaos, and the intensity. The flames to north and south, the dead bodies everywhere, the naked ascetics smeared in ash.

But I met a Tibetan Buddhist monk there—not from a Hindu background—who looked around him in wonder and delight and said, “This is glorious!” All of human life was visible, it seemed—birth and death and everything in between. If paradise were to be found anywhere, he suggested, maybe it existed here, at least as much as in Bali or Tahiti or the Seychelles, the more obvious, and surface-y paradise locations I’d visited.

I gained so much from being in that ancient and powerful location where so many wise souls have studied and taught. With Sarnath six miles away, and scores of pilgrims at the airport off to make the Haj in Mecca.

As I write in the penultimate chapter of the book, set near my home in Japan, “The fact that nothing lasts is the reason that everything matters.”

Check out our in-depth Market Coverage, Business News & get real-time Stock Market Updates on CNBC-TV18. Also, Watch our channels CNBC-TV18, CNBC Awaaz and CNBC Bajar Live on-the-go!

Andhra Pradesh Lok Sabha elections: A look at YSRCP candidates

Apr 25, 2024 6:54 PM

Lok Sabha elections 2024: Banks and schools to remain closed in these cities for phase 2 voting

Apr 25, 2024 5:33 PM

Andhra Pradesh Lok Sabha elections: Seats, schedule, NDA candidates and more

Apr 25, 2024 5:16 PM